I sometimes forget that games consists of many different fields, and in the best of cases, the final product is more than the sum of its parts.

I generally consider myself involved in the fields of a systems-design and programming. So whenever I spot problems while making my games, I tend to use those as my hammers. It is often only after a whole lot of hammering, and sufficient metaphorical smashed thumbs do I remember a fundamental truth; There are more tools than my favored hammers.

Two examples come to mind. In the first, I was bested, and in the second, I prevailed.

Design Problem 1:

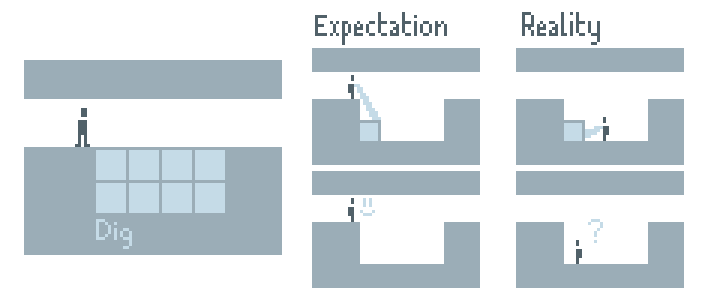

In a colony sim, it is possible for units to get stranded while doing their tasks.

One example would be a scenario where the units can dig upto two cells away from

them, but can only climb up one cell. So when there is a 2 cell deep hole, if they

climb inside the hole, they might dig the cell that was their only way out.

Another variant of this is where they build a wall that locks them out of their base.

So I spent a very normal amount of time (It was not excessive at all, don’t you dare try to imply that it might have been…), figuring out solutions for this.

There were two ways to go about it in my mind. Either we prevent the player from ever giving such a command, or we ensure that the instructions are carried out in such a way that units do not get stuck.

Either way, we need to start by detecting if a particular set of instructions might end up causing a unit to get stranded. And that got complicated quickly.

Based on how the systems are organised, each unit will have to know what every other unit is doing, and how fast they’re going to do it. Maybe when one starts digging this block out, there is a way out of the hole, but another unit is digging another block, and when both of those are dug out, that would leave a third unit stranded. And that’s the simple case.

The problem felt like a fractal. A fractal where you have to solve for every edge. And as the fans of fractals will tell you, there’s always another edge, and always another edge case.

Solving this problem would likely require the whole system of units and tasks to be designed around having to solve this problem. It’s not impossible, but it’s a huge constraint, and ends up limitting other things that you might want to do with the systems.

So I ended up not going for the technical solution. I looked at how some other games solve the problem, and understood why that’s probably the best way to do them.

The Solution:

Let them get stranded.

It sounds insane. It sounds like it could get exceedingly frustrating. But there is a secret to really make it work, possibly a lot better than any other solution.

Make them cute.

Do you seriously expect me to believe that you would just leave these cuties stranded out there? What are you? Some kind of monster?

And there’s the real solution. We had to use two other strengths of game development to solve the problem.

Firstly, art. Make them look sad and helpless, and the player is not going to feel frustrated, rather more motivated to rectify the solution.

Secondly, emergent story telling. These kinds of scenarios will lead to player driven stories of how they had to deconstruct entire large scale constructions just to save one precious beaver/duplicant.

Generally once the you understand that it is possible for units to get stuck, you will ensure that you are more careful when issuing commands, and the problem is largely solved.

We tackled a very hairy technical problem, and found an alternate solution that arguably has more upside than actually solving the technical problem. Also this doesn’t necessarily mean that we don’t try and make the units a little smarter, just that we don’t have to solve every last fractal edge case.

Design Problem 2:

In a puzzle game, the player might accidentally solve a level, and not learn the mechanic that actually solved it.

There are many kinds of games where this can happen. Maybe a point and click where the player is clicking all over the place. Something systemic, where you don’t know how you triggered the thing. Or anything involving button mashing.

But the case that I managed to solve was what I saw in KCPS.

In KCPS, the player starts off setting up all the elements in the games that they have control over, and then hits play, and the level playes itself out. Due to the nature of the mechanics, and my particular design aesthetic, there were several scenarios where the player places things wherever there is space to. They either expect something different to happen, or expect to be wrong, but the level plays itself through, and it is solved. The player now finds themselves back on the level-select screen.

So oftentimes, the level has been solved, but the player doesn’t know why. And while some players reopen the level and actually try and figure out how it is that they managed to solve the level, I think, the natural instinct is to move on to the next level. And in a puzzle game where mechanics tend to build on top of each other, that can certainly be an issue.

I tried the standard things; rather than quitting the level, show them a level complete screen. So then the friction to go back and look at the solution is reduced. But the friction was still there. What I actually needed was there to be friction to exit the level…

The Solution:

When the player completes a level, reset the level.

It just worked. It’s very counterintuitive, and the first time it happens, players are a little confused. But it is right at the start of the game, and they just manually exit out of the level. And then they never think about it again. Like the first solution, we got them habituated to having to leave the level once they have completed it.

The benefits are huge. Now there is more friction to leave the level than there is to verify the solution and figure out why it worked. Your mouse is hovering over the button that allows you to verify the solution. To leave the level you have to move it all the way across the screen.

If there is one piece of design I am proud of, that’s it.

This solved a real onboarding problem, what felt like a problem with the difficulty curve, and we solved it using UI/UX.

Conclusion:

Overall I think these two examples are an interesting contrast. In one case, we embraced the best practise, and applied what everyone else was doing. In the other case, we totally rejected it.

Thinking over these examples is always inspiring for me. It shows how the smallest details can completely change how your players think about your design, and often, these can come from what seem like disparate elements. Every element can affect every other element, and that’s what I am coming to appreciate about this medium. This emergence, where systems interact with each other to create something greater than the sum of their parts, that’s why I do what I do. Getting to see these tiny moments of emergence feels like peeking into the mysteries of the Universe, and actually getting something out of it. And I can think of no better way to spend the rest of my life.